Editor’s note: The following article with photos is from Karina Satomi Matsumoto‘s Okinawando blog, translated from Portuguese to English. -Jim

Hajichi – the tattoo of the Okinawan woman

okinawando / March 21, 2017

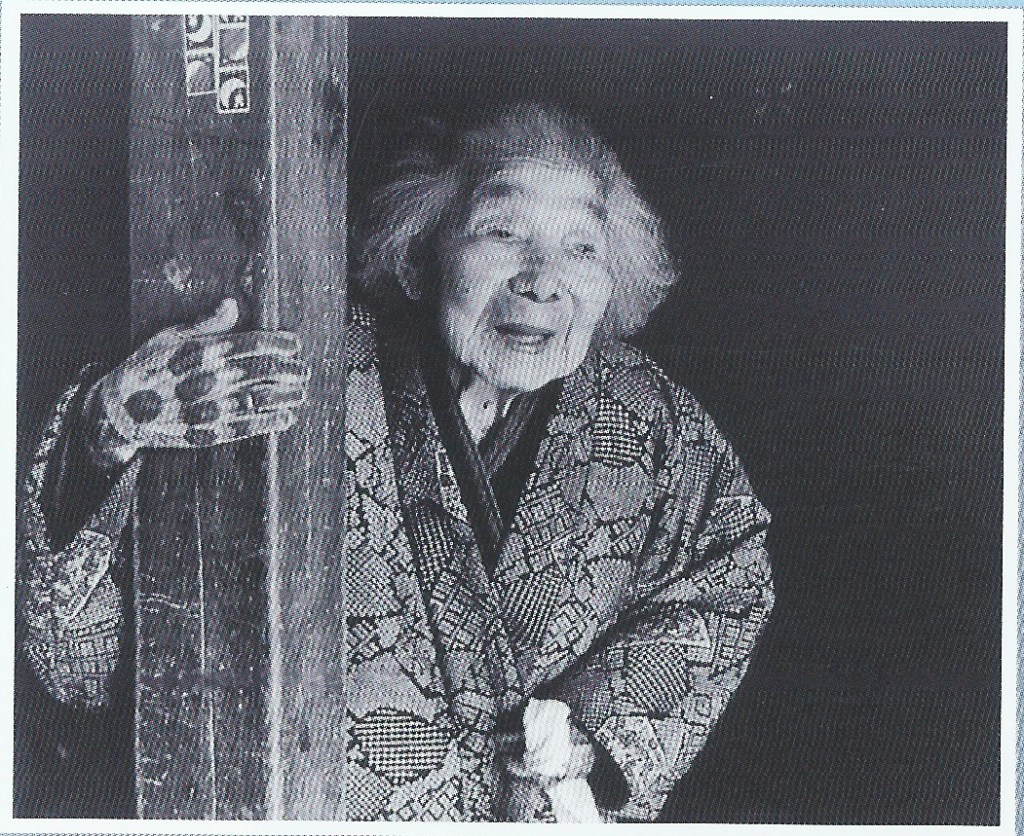

This is my obá’s family – the Yagi family. Sitting on the left are his parents (my great-grandparents) and around him are his brothers (my great-uncles). And sitting there, dressed in black, are her grandparents – my great-great-grandparents. My oba is standing between them, to whom she was very attached. She always tells me family stories and has many photos saved, but there was one thing she had never told me – that my great-great-grandmother had hajichi, the tattoo that Okinawan women had in the past.

– But hey, why does she have that tattoo?

– Every obá had it.

– But why?

– Oh, I don’t know, I never asked.

– And when she came to Brazil, did anyone say anything about her?

– I don’t think so… I never heard anything.

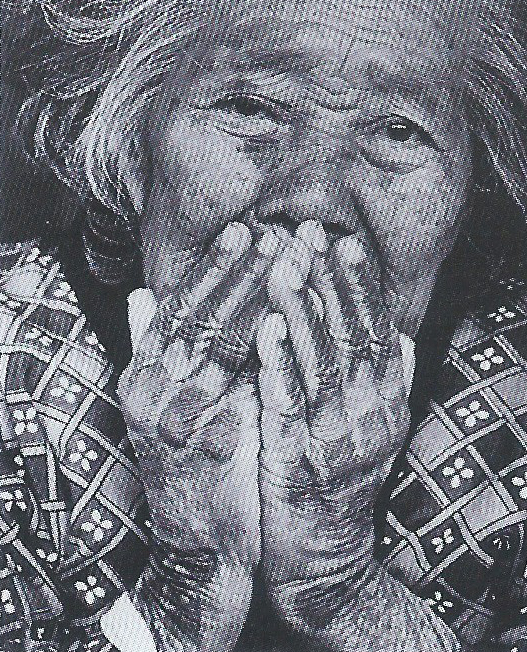

Talking about hajichi is a very difficult task, as there are no more living sources – what is known today is the result of previous research and photos, many of which are unclear and in black and white. There are several hypotheses and sometimes conflicting information; and in addition, it is known that there was a lot of variation according to the region. All of this makes writing about the subject a complicated – and also challenging – task.

Origin – where did hajichi come from?

Hajichi existed on the Ryukyu Islands, having different names depending on the region.

- Okinawa and Amami : hajichi (ハジチ), hajiki (ハジキ), fajichi (ファジチ), pajichi (パジチ)

- Miyako : pizukki (ピヅッキ), pizuki (ピヅキ), paatsuku (パーツク), parikku (パリック), paitsuki (パイツキ), haidzuchi (ハイヅチ)

- Yaeyama : tiku (ティク), tishiki (ティシキ)

- Yonaguni : hadichi (ハディチ)

In this text we will call it “hajichi” (read “raditi” – as in mouse , money , hand ).

The origin of hajichi is uncertain, but travel records indicate that it was already a custom that existed in the 16th century. As for its extinction, it is also not possible to pinpoint precisely, but it is very likely that the last woman with hajichi died at the beginning of 1990s.

Within Japan, the Ainu people (Hokkaido region) and the Ryukyu people are ethnic groups that adopted the practice of tattooing. Looking at other nearby places, such as Taiwan, Philippines, Micronesia, Indonesia, New Caledonia, Polynesia, Australia, New Zealand, there are several people who tattooed (or tattooed) their bodies, which favors the hypothesis that the custom came from the south , considering the long history of trade and exchange that existed in the region. Fuyuu Iha, considered the father of Okinawan studies, also believed that hajichi has its origins in Polynesian and Indonesian customs.

However, it is not known when hajichi appeared in the Ryukyu Islands. It is likely that it began as a way of distinguishing noble women with religious functions, being later copied by other women, which is believed to have only happened in the modern era. Already at the beginning of the Meiji Era (1868), probably all women, from prostitutes to traders, had hajichi.

There is another hypothesis, according to which, with the extinction of the Kingdom of Ryukyu (1879) and the migration of the samuree class (nobility) and their culture to the interior, there was also the migration of tattoo artists to more distant parts, taking their work and spreading the custom of hajichi.

Objective – why did women mark their bodies?

According to research, there were a variety of justifications for women performing hajichi. The best-known version (on the main island of Okinawa) is that women performed the hajichi to show that they were married. However, research carried out by the Yomitan History Museum based on interviews with women on the main island found different reasons, such as:

- If she didn’t, she would move away from her homeland and be taken to Yamato (Japan): 47%

- If I didn’t do it, I wouldn’t go to heaven after death: 15.2%

- They all do it (custom): 18%

On Miyako Island, the result was different:

- Entrance to the world there (after death): 36.5%

- Aesthetics: 14.2%

- Mischief: 12.5%

- Custom: 10.4%

Also according to this research, the age at which they got tattoos varies as follows:

- Less than 10 years: 31%

- 11 to 14 years old: 15.3%

- Don’t know: 18%

Regarding the completion of the tattoo, there is the following data:

- Finished the drawing before getting married: 30.5%

- Finished the drawing after getting married: 12.5%

- Started before marriage and never finished: 55%

- Started after marriage and never ended: 2%

Thus, it is possible to state that almost half of the women (46%) started hajichi before turning 15, therefore being very young. Furthermore, 85% of women said they started hajichi before marriage (whether they finished the process later or not). In research carried out on other islands, around 70% of women got a tattoo before the age of 18.

By performing the hajichi, the girl became recognized as a woman in society. It was also a rite of passage that marked the initiation into marriage – an independent life and the building of a new family.

There are poems (ryuka), which demonstrate that the girls eagerly awaited such a rite. It is believed that not only girls, but also their parents and married women expressed their feelings through these poems:

Mom, mom… Dad, dad…

Give me a glass of rice

I’m going to get a tattoo

I want to get a tattoo

(Ryuka from Okinoerabu, currently part of the Amami Islands, Kagoshima Prefecture)

Get married, just once

Die, just once

The desire to have a tattoo on your hand

It’s for the rest of your life

(Ryuka from Tokunoshima, currently part of the Amami Islands, Kagoshima Prefecture)

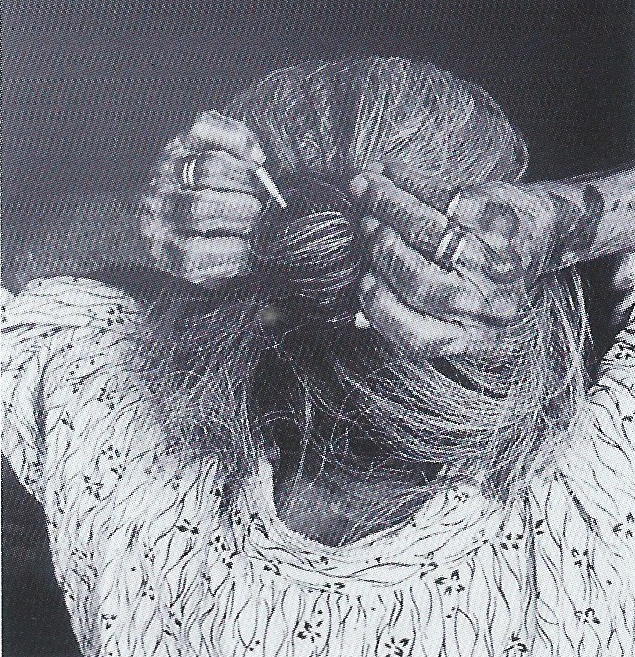

Procedure – how hajichi was done

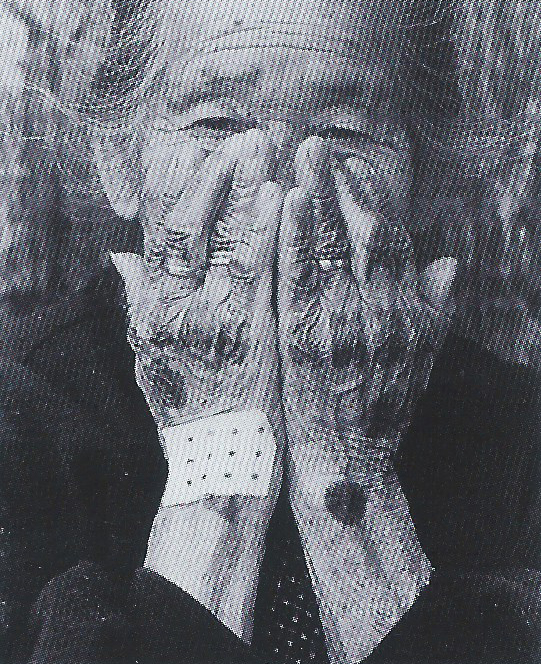

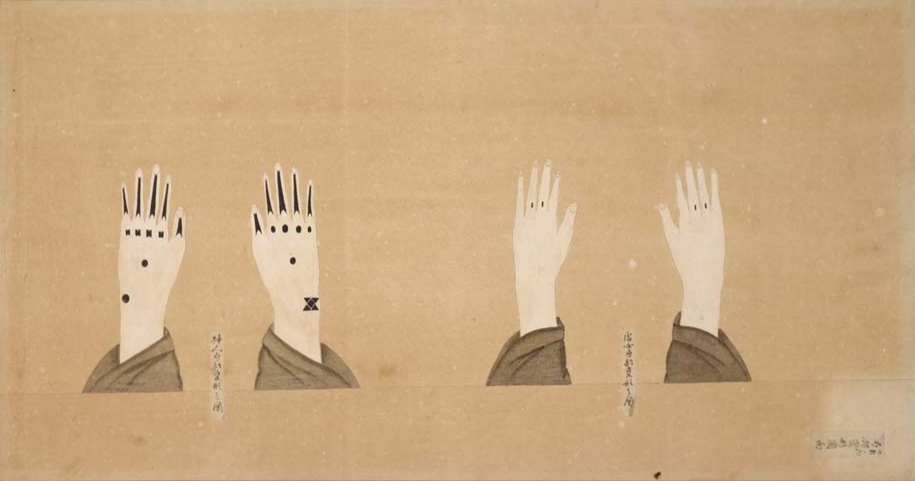

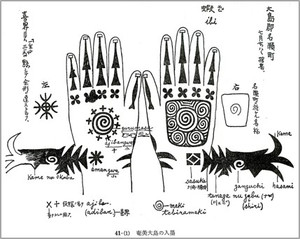

On the Ryukyu Islands, tattoos were usually done on the back of the hand, fingers and forearm. Among the Ainu, it was customary to tattoo the part around the mouth, hands and wrists.

To print the hajichi on the skin, sewing or bamboo needles were used. Paint was mixed with sake and the drawing was painted. There are reports of cases in which more than 20 needles were used at once, which could be joined together in a circle or in a row.

The practice of hajichi was not just about making random drawings in dark blue; the region determined the pattern to be reproduced. Some designs were circles, arrows and the “x” and “+” signs, which were symbols of protection.

As they are relatively remote and have some characteristics of their own, it is possible to generally define some standards for each island or region. However, it is not known what the reasons for the differences are and when they began. Even if there are small variations, it is possible to say that the designs were transmitted from generation to generation within a certain area.

The designs were also a reflection of social status. The further away from the city, the rougher the features. Upper-class women had designs with thin, modest lines. Lower class women had patterns with thick lines and large figures. Even with these differences, it can be said that the custom of hajichi extended to all women.

The person who performed the hajichi was a person known as “shijutsushi” (surgeon) or hajichaa. The work, semi-professional, was paid. But there were also requests based on friendly relationships, in which the work was carried out for free. According to research by the Yomitan Museum, many do not remember payment or report that there was no payment.

Prohibition – why was hajichi extinguished?

At the end of the 19th century, the Meiji government aimed to strengthen the foundations of its Nation State, turning its eyes outwards. With the aim of unifying the nation, he planned the standardization and “Japanization” of Okinawa customs. Competing with the developed nations of Europe for control of Asia, Japan aimed to demonstrate the strength and stability of its central power, and therefore took several emergency measures, such as recruiting soldiers and reforming education.

Thus, there was an attempt to exterminate the culture of the Ryukyu people. The Meiji government aimed to impose a model of Japanese citizen – one recognized by the state, with a unique culture common to all. With their regional culture extinct, the new citizens would have the same body (extinction of tattoos), the same standard language (with the prohibition of uchinaaguchi) and the same customs. Religious practices were also prohibited.

The use of hajichi was officially prohibited in 1899 (Meiji 32), with the “Tattoo Prohibition Order”. However, a few years earlier, in 1880 (Meiji 13), an article containing several prohibitions had already been issued with the aim of “improving customs”. In this sense, hajichi was not only considered an “ethnic custom”, but also a behavior deviating from the public and moral order of the time. However, with weak supervision, it did not end immediately.

How did the newly formed Okinawa Prefecture react? Interestingly, many Okinawans also recognized the need for Japanization. In the same year that hajichi was banned, in the village of Kijoka, in Ogimi (northern region of the island), authorities met and decided to take steps to reform customs. The following practices were prohibited: singing loudly in the village, playing sanshin in the street and having hajichi.

At the time, the newspaper Ryukyu Shimpo began to take greater care with writing and manners and cited the need to police those who broke the rules, even while recognizing the difficulty of abolishing old customs. After a few days, the newspaper even published the names of 3 surgeons who had broken the rules and 2 girls who had tattooed the hajichi. A letter from a reader, published in the newspaper, says that the reason the ban did not take effect is the existence of many surgeons, who were spreading lies, such as that, if they did not have hajichi, women would be taken to other provinces or would be taken to be soldiers’ wives. The reader also says that supervision had become weak and people were carrying out procedures at night, away from the eyes of neighbors, and that he wanted greater control.

Not only in Okinawa and Japan was the practice of hajichi being policed – with immigration, tattooed women also encountered difficulties. There is a report that two women with hajichi were on a ship. Women from other provinces, embarrassed to show Japanese women looking like that to foreigners, forced the Okinawan women to lock themselves in their room and banned them from going on deck until they arrived in Honolulu. Another case occurred in the Philippines, when a rumor spread that there were three Okinawans with hajichi, generating discomfort among other Japanese immigrants. After a meeting called by the local Okinawa Association, the three were sent back to their homeland.

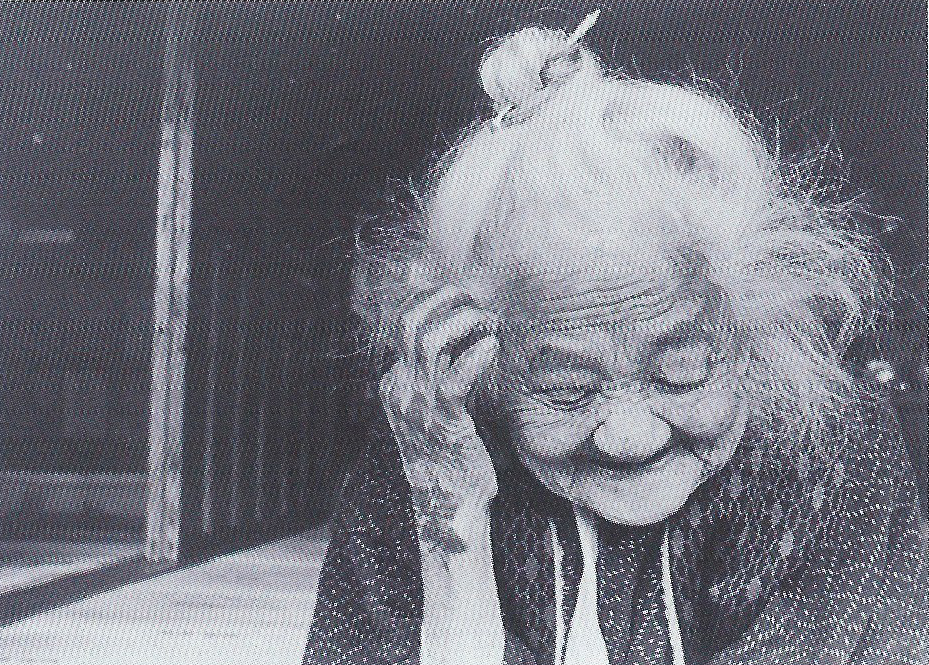

At the beginning of the 20th century, the practice of hajichi was no longer common. During the war, when my obá was a child, tattoos were a mark of older women. Currently, all that remains are photos, scant information and memories that some people keep of their grandmothers. Unfortunately, like so many other aspects of women’s history, the custom of hajichi has not been well documented (or the writings have not survived). But luckily, even though I don’t have much information about the story or my great-great-grandmother’s hajichi, I have her photo. Even though I don’t know much, how cool it is to look at the photos and see a little of the history of our ancestors, the women of Ryukyu.

Source:

「琉球の記憶 HAZICI」 山城博明・波平勇夫 新星出版 2012年 [“Memories of Ryukyu HAZICI” Hiroaki Yamashiro and Isao Namihira Shinsei Publishing 2012]

「ハジチのある風景」 比嘉清眞写真展 那覇市歴史博物館 2010年 [“Landscape with Hajichi” Kiyomasa Higa Photo Exhibition Naha City Museum of History 2010]

Editor’s note: The following article with photos is from the Kanasa blog. -Jim

Hajichi: The Powerful Female Tattooing Tradition of the Ryukyus

Due to society being conditioned to believe a particular standard or ideal of beauty, we forget the beautiful cultural traditions that women once practiced to preserve their beauty that were vastly different to the standards we see today.

Dominant cultural beliefs often undermine the beauty of difference, and that can be said for the hand tattooing traditions of the Ryukyus.

Hajichi was a commonly practiced tattooing tradition in the Ryukyuan Kingdom, before the annexation of the Ryukyu Islands during the Meiji Restoration of Japan. The tattoos vary in nature, patterns, and shapes are largely determined by Island, giving each tattoo design its unique distinction between the others.

Hand tattoos were only worn by the women of the Ryukyus, and the practice strictly lied in female culture.

The tattoo artist, also known as a Hajitiya used a sharpened bamboo stick as the needle, dipping it in a charcoal-based ink mixed with the traditional Ryukyuan spirit, awamori.

History of Hajichi

Not much is known about how the practice of female-only tattooing came about. Considering the geographical location of the Ryukyus and how the Ryukyus served as an important cultural & trade route between Southeast & East Asia, it’s entirely plausible that we were influenced by the tattooing culture found in the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia & Samoa.

Travel records have shown that Hajichi was a practice performed since the 16th century. Some historians theorize that Hajichi was brought over by the noble class, with the practice subsequently passed down the classes.

At the beginning of the Meiji Era (1868) women from all professions and economic classes believed to have Hajichi.

From Mother to Daughter: The Reasons for Hajichi

In modern day Ryukyu, there are many beliefs held about the reasons behind a woman’s decision to get Hajichi.

Some mistakenly believe that it was purely for sexist reasons such as ‘marking’ a woman once they had gotten married.

However, research showed that there were many different reasons behind a woman’s decision to get Hajichi, such as:

- The fear that if one did not get Hajichi, they would get taken to Yamato (mainland Japan) – 47%

- The fear of not going to heaven – 15.2%

- Other: 18%

In Miyakojima, the results were contrastively different to the other islands’ responses:

- An affirmation that one was going to heaven after death – 35.6%

- For aesthetic purposes – 14.2%

- Mischief – 12.5%

- Other: 10.4%

The research also highlighted how many women had Hajichi whilst they were very young, indicating that it was something done during a woman’s youth, rather than solely for the sanctity of marriage.

This also suggests the beautiful nature of how Ryukyuan society was not as vigorously patriarchal compared to other cultures.

Hajichi tattoo by age:

- Less than 10 years old: 31%

- 11 to 14 years: 15.3%

- Don’t know: 18%

Regarding when the Hajichi tattoo process, the respondents answered:

- Finished drawing before getting married: 30.5%

- Finished drawing after getting married: 12.5%

- It started before the wedding and didn’t end: 55%

Research first published from Okinawando

The Meanings behind Hajichi

Hajichi was also done when a woman got married, fell pregnant, or when a woman hit certain milestones such as turning 60 years old.

The tattoos consisted of cross-shaped patterns and dots, as well as flower and star-like patterns.

Some say that the designs were drawn following the stars seen by the Hajitiya in the night skies.

Hajichi bears similarity to tattoos of other pacific islands such as Samoan, Taiwanese, and Palauan tattoos, which could be due to the trading relations Ryukyuans had with many Pacific kingdoms aforementioned.

It is said that the Ryukyuan Kingdom had at around 44 embassies, such as in Siam, Java, Luzon, Sumatra, and Borneo.

Other kingdoms Ryukyuans came into contact with included kingdoms in the Pacific, the dynasties of China, and the Philippines.

Is Hajichi still practiced today?

Unfortunately, due to the suppression of practices such as these, which did not fit into the status quo of Japanese hegemony, Hajichi is seldom practiced in the Ryukyus.

Many of the women who have them have now passed, and many have adopted the belief that tattoos are unruly, as this is the common belief people hold in Japan.

In mainland Japan, tattoos were often associated with Yakuza who are Japanese gangs.

However, it’s not all bad news as young Ryukyuans are increasingly becoming more in touch with their ancestral roots, finding a newfound connection with cultural practices once deeply suppressed and condemned. Much like the strong indigenous spirit of our Brothers and Sisters in Hawai’i, Samoa, and America, the Ryukyuan youth are paying homage to the sacred spiritual roots that make the Ryukyus the special place it is.

One example is Morika Yoshiyama, an artist from Okinawa city has defied the cultural standards of Japan and made the decision to get Hajichi.

‘I imagine the feelings of my ancestors, and it’s my joy to have been born as an Okinawan’ she explained, in a piece in Asahi.

In the same article, photographer Hiroaki Yamashiro hoped that this revival will provide ‘an opportunity for tattoos to be re-evaluated as a tradition and people’s personalities’.

Lee A. Tonouchi, a Ryukyuan born and raised in Hawai’i recently published a book called ‘Okinawan Princess: Da Legend of Hajichi Tattoos’ which explores the beauty and history behind Hajichi tattoos through a children’s book. It is illustrated by Laura Kina.

You can buy a copy via an independent Hawaiian publisher here. We find the tattoo designs exceptionally beautiful, and I’m even personally considering getting one purely for the basis of preserving my fascinating culture and celebrating a unique idea of beauty.

How to Say ‘Hajichi’ by Island Languages

- Okinawa and Amami : hajichi (ハ ジ チ), hajiki (ハ ジ キ), fajichi (フ ァ ジ チ), pajichi (パ ジ チ)

- Miyako : pizukki (ピ ヅ ッ キ), pizuki (ピ ヅ キ), paatsuku (パ ー ツ ク), parikku (パ リ ッ ク), paitsuki (パ イ ツ キ), haidzuchi (ハ イ ヅ チ)

- Yaeyama : tiku (テ ィ ク), tishiki (テ ィ シ キ)

- Yonaguni : hadichi (ハ デ ィ チ)

Additional Resources:

Lee A. Tonouchi, “Hajichi Stories — Tree Local Women Tell Why Day Got Their Okinawan Hand Tattoos,” Discover Nikkei, 7 Sep. 2023. This article was originally published in The Hawai’i Herald on 18 Aug. 2023.

Robert Kajiwara, “About Hajichi: Indigenous Luchu (Okinawan) tattoos,” Peace for Okinawa Coalition website, 12 Apr. 2022.

The Secret History of Okinawan Tattoos, JANM, 27 Aug. 2015.

Noah Oskow, “Hajichi: The Banned Traditional Tattoos of Okinawa,” Unseen Japan, 28 Apr. 2021. [Includes links to videos.]

Michelle Ye Hee Lee and Julia Mio Inuma, “In Okinawa, a push to revive a lost tattoo art for women, by women,” Washington Post, 25 July 2022.

Kim Kahan, “Reviving a Stigmatized Tradition: Tattoos from Okinawa, an Interview with Hajichi Project’s Moeko Heshiki,” Metropolis Japan, 28 Feb. 2022.

Kazuyuki Ito, “Once outlawed, Okinawa’s ‘hajichi’ tattoo culture revived,” Asahi Shimbun, 20 Sep. 2019.

“How one young woman is reviving Okinawa’s forgotten body art,” Tatler, Agence France-Presse, 20 Feb. 2023. Features hajichi tattoo artist Moeko Heshiki. Free sign-up to read the full article.